Project Assumptions & Risks

Assumptions and risks are embedded in our daily lives. We expect the day will unfold as planned, and risks will not materialize. Most of these assumptions are benign, like thinking the weather report will be accurate; or no major calamities will occur.

Projects are built on assumptions. Without them, it would be impossible to proceed. But some may lead to unanticipated or even tragic consequences. The root cause of catastrophic failures is often traced to flawed assumptions or poor risk management.

Technicians raised questions about the Hubble space telescope’s design, but they assumed the specifications were correct. Failed test results were dismissed because it was believed the testing equipment was at fault. NASA program managers decided to launch the space shuttle Challenger despite warnings (risks) that the O-ring seals may fail in cold weather.

Risks & Assumptions

An assumption is an idea that is accepted to be true without certainty. Until we validate assumptions, they also represent a risk.

Risks are future events that have a likelihood of occurrence and an anticipated impact. Risks can be opportunities (positive) or threats (negative). Frequently we focus on the negative and fail to consider the upside.

Risks can be described quantitatively or qualitatively. Likelihood can be expressed as a probability or with descriptive modifiers. For example, “the chance of rain is 75%” or “it is likely to rain today.” Impacts can be measured numerically in days or dollars, or qualitatively (e.g., late, over-budget).

Project management has frameworks for managing assumptions and risks. Assumptions are documented in the assumptions log, tracked, validated, and the outcome communicated. Risks are recorded in the risk register, assessed, addressed, monitored, and responded to. Adhering to these practices will ensure better project outcomes.

Knowns & Unknowns

Most people struggle to define assumptions without using the word “assume.” An episode from the Odd Couple TV show offers an amusing definition of assUme. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s known-unknowns press conference is another example.

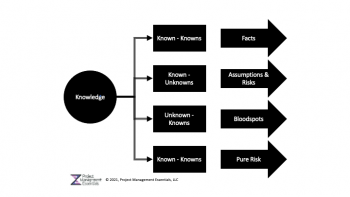

A matrix of what we know and don’t know provides insight into assumptions and risks:

| KNOWN | UNKNOWN |

KNOWN | I know that! | Assumptions & Risks |

UNKNOWN | Bias. Blind spots | Pure risk. Unexpected. |

- Known-Knowns are things we know with certainty. We can count on them occurring. They are neither risks nor assumptions.

- Known-Unknowns can either be assumptions or risks.

- Unknown-Knowns are things we did not realize we knew. These are blind spots.

- Unknown-Unknowns are outside our realm of knowledge and represent pure risk.

Unvalidated assumptions are known-unknowns and should be documented in both the assumptions log and risk register. These risks may also be included in the contingency risk reserves. Expected monetary value or similar valuation techniques can be used to estimate the time or cost impact of these risks.

The impact of the unknown-unknowns is incorporated into the management reserves or buffer. Buffers are commonly percentages applied to the estimated cost or time. For example, the cost of a home renovation project may exceed the original budget by 10-20%; or take an additional 4-6 weeks to complete.

Assumptions & Cognitive Bias

Cognitive biases are shortcuts the brain makes to solve problems quickly. Formally, they are defined as systematic deviations from the objective reality based on our perceptions. In other words, we create our own perceptions of reality. For example, we look outside and see a bright, sunny day and assume it is warm.

Cognitive bias creates risk. They are blind spots and unrecognized assumptions. Since we do not realize our biases, we fail to document and systematically address them.

Anchor bias is placing undue weight on the first piece of information received. Project costs and durations are often compared to the imprecise, initial, high-level estimates. Problem-solving sessions often fixate on the first ideas presented and fail to consider all possible causes.

Confirmation bias is favoring information that conforms to our existing beliefs. Rather than assessing new data and reevaluating our expectations, we subconsciously filter out the dissonance. Crises feel unexpected because telltale signs are ignored. For example, the construction of a building is behind schedule, and the weather is worse than expected, yet we are surprised when milestones are missed.

The sunk cost fallacy often afflicts troubled projects. It is the belief that investing additional resources on a failing project will turn the tide. Colloquially, this is known as “doubling down on a bad bet” or “throwing good money after bad.” Sometimes projects just need to be put out of their misery.

Cognitive bias may have a limited impact on small, simple projects because events are well-understood. However, on complicated and complex projects, these blind spots can be a significant source of risk. This is because fact patterns are novel, and it is difficult to predict the dynamics of future events.

Managing Assumptions & Risks

Standard project management practices can be used to handle assumptions and risks. The size, scope, scale, complexity, and risk profile of the project will influence the tailoring of these practices. A project with life and death implications, such as developing a new drug, will obviously require a more rigorous regimen than creating a computer game.

Best practices include:

- Create an assumptions log and risk register that are readily accessible and transparent to the project team and impacted stakeholders.

- Proactively recognize assumptions and risks. New items will be uncovered in meetings, informal conversations, emails, and project documents. Be sure to add them to the assumptions log and risk register.

- Categorize and prioritize the assumptions and risks. For both assumptions and risks, priority should be based on impact and urgency (e.g., how soon they need to be addressed); risks should also be prioritized based on the likelihood of occurrence.

- Assign owners and due dates for each item. Owners are accountable for addressing the items, and due dates drive timely resolution. Risks may require several owners and dates.

- Actively manage the assumptions log and risk register. Regularly review open items and follow up on outstanding actions. Close items that are no longer relevant.

- Communicate outcomes to appropriate stakeholders to ensure the right people have the right information to make effective decisions.

- Periodically review assumptions and risks. Changes in the project or business environment may change their urgency, priority, or impact. Review closed assumptions to confirm validity. Review risks to ensure their applicability and the effectiveness of the response strategy.

Actively managing project assumptions and risks are a defense against the unknown. Documenting, evaluating, and addressing these items creates awareness and discipline. Unexpected events may still arise, and you will be better prepared to respond.

© 2021, Alan Zucker; Project Management Essentials, LLC

See related articles:

· Peering into the Crystal Ball: 7 Tips for Successful Project Risk Management

· Project Status is Subjective: Linguistic and Cognitive Bias

· Projects and Probabilities—A Dangerous Combination

· Rain, Flight Delays, and Risk Management

To learn more about our training and consulting services, or to subscribe to our Newsletter, visit our website: http://www.pmessentials.us/.

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version- Login or register to post comments

Send to friend

Send to friend